“There’s strange and wonderful stuff in this lifetime of Lou’s music,” I wrote in 1987, under the spell of the Cabrillo Festival. “Much of it is so damned beautiful, so open-handed and eager to please.” Just arrived from New York, where open-handed newness was the brand of the musical sissy, I found Lou’s big diatonic C-major symphonies startling at first but for the wrong reasons. I asked him, for a documentary I was producing for KUSC, what were the distinguishing features of a California composer.

“There’s strange and wonderful stuff in this lifetime of Lou’s music,” I wrote in 1987, under the spell of the Cabrillo Festival. “Much of it is so damned beautiful, so open-handed and eager to please.” Just arrived from New York, where open-handed newness was the brand of the musical sissy, I found Lou’s big diatonic C-major symphonies startling at first but for the wrong reasons. I asked him, for a documentary I was producing for KUSC, what were the distinguishing features of a California composer.

“I suppose,” he answered, “ it’s that we’re not afraid of sounding pretty.”

Lou’s Piano Concerto, out of which Marino and Gustavo whaled the daylights at Disney Hall last week, is strange, wonderful, spellbinding and gorgeous. It has a feel-good slow movement whose pure and simple…well, prettiness, can wash away all your sins. Its finale, which demands a clobbering from the soloist’s fists and forearms that could be considered pretty only by a demonic chorale. Its tuning is the ancient system of “Just Intonation” that Lou sought to revive (along with Esperanto) that maintains a soft and lovely haze between you and the music. It is a very knowing music; it knows about jazz and ancient dances and also about contemporary licks. Those two guys, Marino and Gustavo at Disney Hall, took full possession.

Lou’s Piano Concerto, out of which Marino and Gustavo whaled the daylights at Disney Hall last week, is strange, wonderful, spellbinding and gorgeous. It has a feel-good slow movement whose pure and simple…well, prettiness, can wash away all your sins. Its finale, which demands a clobbering from the soloist’s fists and forearms that could be considered pretty only by a demonic chorale. Its tuning is the ancient system of “Just Intonation” that Lou sought to revive (along with Esperanto) that maintains a soft and lovely haze between you and the music. It is a very knowing music; it knows about jazz and ancient dances and also about contemporary licks. Those two guys, Marino and Gustavo at Disney Hall, took full possession.

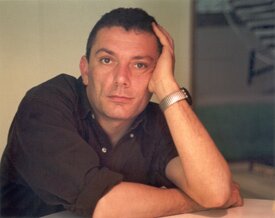

It’s nine years – amazing! – since Marino Formenti took his place on our horizon. He came here first with the ensemble Klangforum Wien, which had taken charge of the festival “Resistance Fluctuations.” Dorrance Stalvey, who ran the Monday Evening Concerts, spotted the 34-year-old Marino for his solo potential, and booked him for a recital series that took off like Gangbusters; Formenti has been in orbit ever since. He heads now for San Francisco, to play Messaien’s vast devotional exercise Vingt Régards. Lucky San Francisco.

THE BRAHMS RUSH

AIMEZ-VOUS BRAHMS? MOI NON, MAIS…. I am not in the habit of linking the lumpy clods that are the music of Johannes Brahms to words like “exquisite,” but hear me out this once. Meandering among the clods of of the Second Symphony at Disney Hall last weekend, in a Berlin Philharmonic performance of uncommon elegance and clarity, my attention was engaged by a sudden burst of music truly exquisite. I love it when The soothing theme that begins the first movement returns, miraculously unscathed after surviving some brutalizing during the development section, its wounds now gently swaddled in remembrances of a somewhat useless, lacey countermelody that had first been, found then lost some time before. It’s actually a familiar Brahms trick, turning the dramatic return of a long-awaited main theme into an angelic, rhapsodic; moment; he pulls he same trick in the B-flat Piano Concerto, but never as purely exquisite as in this Second Symphony, where it comes on as sweet release after entrapment in mud. You go around deploring the overcooked-meat-and-potatoes of those four symphonies, with a special cringe at the gray-wool stuffing of the First, but then there is Papa Brahms, his warm hand raised against the chill that has beset your spinal column that day, and suddenly life isn’t merely okay…it has become, well, exquisite.

I did find it curious, however, that time and space were granted, on this al-Brahms program, to Arnold Schoenberg’s orchestration of the Brahms G-minor Piano Quartet — which contains some quite ugly writing for horns and winds that merely falsify the music’s greatly respectable source – as if the world needed a Brahms Fifth Symphony, or the Mona Lisa that beard.

Simon Rattle’s Brahms earned him a hero’s cheers, and rightly so. He and his orchestra have grown magnificently. His early days here, as one of two (with Salonen) podium contenders for the L.A. Phil leadership, revealed a revolutionary podium presence, capable of informing the press (meaning me, in this case) that the Phil’s playing was “simply dreadful”and not yet the all-knowing musician he has become. Now he and Esa-Pekka, and a few others, represent a major force to assure the world that symphonies and their orchestras might, after all, endure.

Simon Rattle’s Brahms earned him a hero’s cheers, and rightly so. He and his orchestra have grown magnificently. His early days here, as one of two (with Salonen) podium contenders for the L.A. Phil leadership, revealed a revolutionary podium presence, capable of informing the press (meaning me, in this case) that the Phil’s playing was “simply dreadful”and not yet the all-knowing musician he has become. Now he and Esa-Pekka, and a few others, represent a major force to assure the world that symphonies and their orchestras might, after all, endure.

That was his major accomplishment in his two programs here, demonstrating with his superlative instrument that this ancient, creaking repertory simply requires wonderfully accurate playing to rekindle that old Brahmsian rapture that used to comfort us at our adolescent bedtimes that all this overscored twaddle somehow stood for authentic music. Later in our lives there would be Mozart.

OR, AT LEAST, ROSSINI

Comes yet another supremely delicious bel-canto comedy from the L.A. Opera’s purveyors of the magic touch, this one the finest of that entire repertory of patter song, giggling ensemble and wonderfully giddy maximum-sense nonsense. There’s something about the magic of this enchanting repertory – a message that has caught hold with this home-town, unpredictable opera company. This time, under sublime. California-perfect skies, Rossini’s tidy, splendidly crafted comedy The Barber of Seville achieves a kind of perfection, galvanized by Nathan Gunn’s great opening “Largo al factotum” held in thrall from then on by the full, cheering house.

Comes yet another supremely delicious bel-canto comedy from the L.A. Opera’s purveyors of the magic touch, this one the finest of that entire repertory of patter song, giggling ensemble and wonderfully giddy maximum-sense nonsense. There’s something about the magic of this enchanting repertory – a message that has caught hold with this home-town, unpredictable opera company. This time, under sublime. California-perfect skies, Rossini’s tidy, splendidly crafted comedy The Barber of Seville achieves a kind of perfection, galvanized by Nathan Gunn’s great opening “Largo al factotum” held in thrall from then on by the full, cheering house.

There was perfection in director Emilio Sagi’s staging, superbly balanced to suggest personal values as well as comedic: the sense of absurdity as well as genuine loss by debuting basso buffo Bruno Pratico as the thwarted suitor Bartolo, the subtle chicanery in Andrea Silvestrelli’s thunderous yet vulnerable Basilio the sly fixer – a stupendous re-creation following last season’s hilarious Gianni Schicchi – the marvelous mix of agile mischief and genuine passion in the Rosina of Joyce DiDonato in her long-overdue debut. As the questing Almaviva another welcome debutor, Peruvian tenorino Juan Diego Flores delivered a show-stopping performance of the opera’s killer final aria “Cessa di piu Resistere” often omitted out of mercy but this time reinstated in full glory.

All told, a superb, superbly comic three hours of opera often dealt with as overripe burlesque, here – in the work of debuting conductor Michele Mariotti and director Emilio Sagi – managed with love, respect and an awareness of its antic wealth.

(Photo of Marino Formenti by Betty Freeman)